Empirical SCOTUS is a recurring series by Adam Feldman that looks at Supreme Court data, primarily in the form of opinions and oral arguments, to provide insights into the justices’ decision making and what we can expect from the court in the future.

Please note that the views of outside contributors do not reflect the official opinions of SCOTUSblog or its staff.

In Trump v. CASA, one of the 2024-25 term’s blockbuster decisions, Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s majority opinion frames the dispute around the judiciary’s authority to issue universal injunctions – that is, orders that prohibit the executive branch from enforcing a law or policy anywhere in the country – and sets the tone through a mode of interpretation that blends textualism, originalism, and historical practice. Throughout the opinion, the court warns against transforming the judiciary into an “imperial” branch and highlights the practical consequences of its decision – indicators of what are called structural and pragmatic reasoning.

These interpretive moves exemplify what the Congressional Research Service (CRS) identifies as eight modes of legal reasoning – textualism, original meaning (originalism), judicial precedent, structuralism, historical practice, pragmatism, moral reasoning, and national identity. Though often overlapping in practice, each draws on distinct sources of authority, from grammatical analysis (textualism) to constitutional design (structuralism) to shared civic values (national identity). Given the Supreme Court’s ideological divisions, these interpretive methods serve not merely as tools but as signals of deeper jurisprudential commitments.

Methodology

To analyze these modes empirically, I defined each of them as a measurable category, assigning a 0–20 score based on how often and how integrally it was used in each opinion of the 2024-25 term.

For each majority opinion, I examined the language, citations, and reasoning to identify signs of different interpretation styles – like focusing on the exact words of a law (textualism) or looking to historical understanding at the time it was written (originalism). Each method was given a score from 1 to 20 based on how often and how clearly the mode appears. I then used basic quantitative tools – such as word counts, phrase tracking, and citation mapping – to gather measurable data linked to each interpretive style. These results were then aggregated to produce clear scores that reflect which interpretive methods the justice relied on most, allowing for consistent comparisons across many decisions

Breaking down CASA with this methodology

Barrett’s majority opinion in Trump v. CASA places particular emphasis on the structural and historical limits of judicial power. The central interpretive mode is historical practice (which sometimes overlaps with originalism), and it receives the highest score (19/20) due to Barrett’s repeated insistence that “for most of our Nation’s history,” no universal injunctions were issued, and that “[n]either the universal injunction nor any analogous form of relief was available in the High Court of Chancery in England at the time of the founding.”

Closely supporting this is structuralism (16/20), which frames the case in terms of judicial overreach and constitutional role boundaries. Barrett asserts that “federal courts do not exercise general oversight of the Executive Branch,” and she repeatedly reinforces the court’s institutional limits, aligning judicial power with the original constitutional design.

Originalism (14/20) is similarly instrumental: Barrett interprets the Judiciary Act of 1789 through the lens of Founding-era equity practice, asserting that equitable relief – that is, a court order requiring a party to do something or stop doing something, rather than awarding money damages – today must match those sorts of equitable remedies “‘traditionally accorded by courts of equity’ at our country’s inception.” These interpretive commitments converge in her use of judicialprecedent (13/20), as she marshals several past cases to underscore that nonparty injunctions (orders that provide relief to individuals or entities who are not part of the case) have never been doctrinally legitimate. Textualism (13/20) reinforces this by reading the phrase “all suits…in equity” in the 1789 Act as cabined by its historical context.

Finally, pragmatism (10/20) plays a supportive role, as Barrett notes the proliferation of universal injunctions under recent administrations and warns of their systemic effects, including forum shopping and judicial instability.

Notably absent are appeals to national ethos (0) or strong moral reasoning (5) – Barrett explicitly critiques the dissents for such “rhetoric” and insists the opinion rests on “limits on judicial power.” The result is thus a decisively originalist and historically-bounded account of judicial authority that offers minimal rhetorical flourish and maximal institutional constraint.

Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, concurring

Thomas’ concurrence differs from the majority mainly in the depth and exclusivity of its originalist and structuralist emphasis. Where originalism scores 14 and structuralism scores 16 in the majority opinion, Thomas’ opinion elevates those modes to originalism at 17 and structuralism at 18 by emphasizing that equitable remedies must adhere strictly to the traditional understanding of judicial power at the Founding. His structural reasoning is also more rigid, treating the equitable remedy as inseparable from institutional boundaries imposed by Article III of the Constitution. Thomas’ pragmatism score of 4 is much lower than Barrett’s, as he appears far less concerned with the practical effects of the court’s decision.

Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Thomas, concurring

Alito’s opinion introduces a distinct interpretive mode not deeply analyzed in the majority: the procedural implications of third-party standing and class certification. His focus pushes the structuralism score to 17, slightly higher than the majority, as he is especially concerned with institutional roles and the proper function of procedural doctrines. For instance, he warns: “Left unchecked, the practice of reflexive state third-party standing will undermine today’s decision as a practical matter.” Alito scores 12 for judicial precedent, slightly lower than the majority, as he relies less on stare decisis – that is, the principle that courts should generally adhere to their prior precedents.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh concurring

Kavanaugh is interpretively distinct for his heavy pragmatist reasoning (at 17), far more pronounced than in the majority. He emphasizes the administrative chaos and legal instability caused by universal injunctions, stating that while “uniformity is often essential or at least sensible and prudent,” “disuniformity—even if only for a few years or less—can be chaotic.” Additionally, while agreeing with the textual and historical basis for the court’s holding, Kavanaugh’s structuralism score is slightly lower at 14 because he views the court’s supervisory role more flexibly: He sees interim legal uniformity as being preserved by judicial action, not limited by it. In other words, he is more of an institutionalist than others in the majority.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, dissenting

Sotomayor’s dissent is interpretively anchored in moral reasoning at 18 and national ethos at 17, dramatically higher than the majority, where those modes score 5 and 0, respectively. She centers the constitutional stakes on newborns and systemic harm, asking “[w]hat grave harm does the Executive face that prompts a majority of this Court to grant it relief? The answer, the Government says, is the inability to enforce the Citizenship Order against nonparties.” She leverages judicial precedent at 16, citing United States v. Wong Kim Ark, Plyler v. Doe, Dred Scott v. Sandford, and Califano v. Goldfarb in a way that prioritizes the lived experience of legal deprivation.

Jackson dissenting

Jackson’s opinion diverges most in structuralism, at 19, and moral reasoning, at 20, grounding her dissent in a deep philosophical defense of judicial review and constitutional supremacy. She critiques the majority for enabling “a zone of lawlessness”: “To conclude otherwise is to endorse the creation of a zone of lawlessness within which the Executive has the prerogative to take or leave the law as it wishes.” Her discussion of the rule of law versus the rule of men evokes the foundational constitutional structure, garnering her a structuralism score of 19. She also scores 13 for originalism, albeit unconventionally, by invoking Founding-era rejections of monarchical prerogative as justification for the full judicial enforcement of constitutional limits.

Looking beyond CASA: combined case analysis

As noted earlier, I measured each signed majority opinion of the court from this past Supreme Court term using this methodology. Here are the main findings.

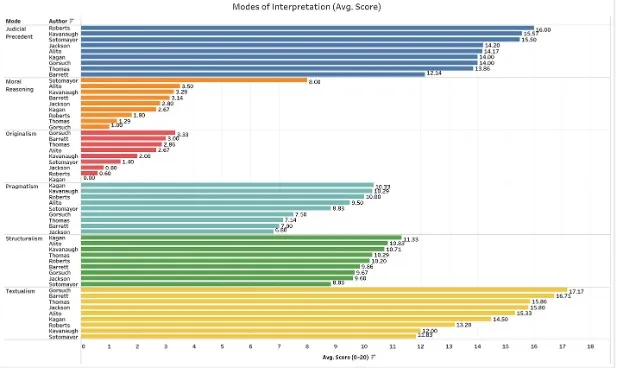

First, look at the average score per mode (from a selection of six of them) per justice. Some of the scores, like those for originalism, are significantly lower because, although they appear prominently in certain cases, the methods of interpretation are not prominently used in most of the decisions:

As shown in the chart, the most frequent and deeply embedded method among the justices is textualism, with Gorsuch (17.17), Barrett (16.71), and Thomas (15.86) leading on average. These scores reflect consistent reliance on a close reading of statutory and constitutional language, application of canons of construction, and emphasis on grammatical structure. In contrast, Kavanaugh (12.90) and Sotomayor (12.00) apply textual analysis with less centrality, though still significantly.

In terms of originalism, a sharp ideological divide emerges. Gorsuch (3.33), Barrett (3.00), and Thomas (2.86) lead in the use of originalist reasoning, while the liberal bloc – Jackson (0.60), Sotomayor (1.40), and Justice Elena Kagan (1.80) – score notably lower, rarely invoking Founding-era meaning or the Framers’ intent in their constitutional reasoning.

On judicial precedent, there is broad engagement across the bench. Chief Justice John Roberts tops the scale (16.00), with Kavanaugh (15.50), Sotomayor (14.20), and Jackson (14.17) close behind, reflecting a deep integration of case law as an anchor for constitutional and statutory holdings.

Finally, structuralism – a method concerned with institutional design and the separation of powers – shows high scores from Kagan (11.33), Alito (10.83), and Kavanaugh (10.71).

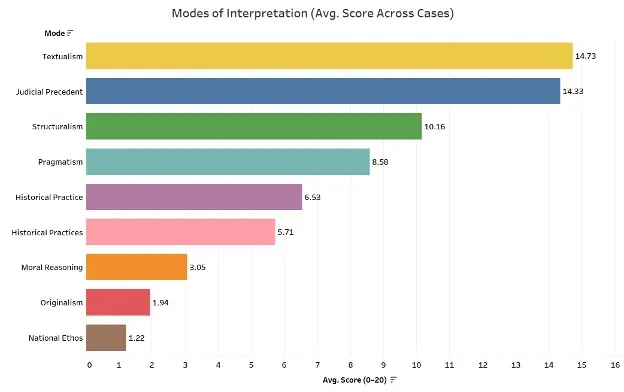

The next graph maps the average use of each mode across cases:

The most prominent finding is the dominant reliance on textualism (14.73) and judicial precedent (14.33), which together form the interpretive backbone of most opinions. This suggests the court heavily favors grounded, rule-based methods that prioritize the statutory or constitutional text and prior case law, reinforcing continuity and doctrinal clarity.

Structuralism also features strongly (10.16), reflecting the court’s recurrent use of constitutional design – particularly federalism and separation of powers – to support its reasoning. Pragmatism follows (8.58), showing moderate engagement with the real-world consequences and policy effects. The historical practices method (5.71) ranks lower, indicating a limited but meaningful use of tradition and custom.

Strikingly, originalism scores quite low (1.94), suggesting its rhetorical prominence in public discourse far exceeds its actual frequency in written opinions. Even lower is national ethos (1.22), and moral reasoning (3.05), reflecting a court more invested in institutional logic than ethical or identity-based appeals.

What this analysis shows

The 2024–25 Supreme Court term was defined by the outsized influence of President Donald Trump’s re-election and a wave of ideologically charged disputes over executive power, immigration, civil rights, and the limits of judicial relief. Across this docket, the justices’ approaches to interpretation revealed distinct patterns. The court’s conservative bloc, particularly Thomas, Alito, and Barrett, leaned more heavily on originalism and textualism. Their opinions frequently referenced Founding-era sources, emphasized the fixed meanings of legal texts, and avoided pragmatic balancing. By contrast, the liberal justices – Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson – more frequently deployed pragmatism and moral reasoning, often grounding their opinions in the real-world consequences of rulings and appeals to justice, fairness, and civic values.

Yet, these interpretive scores are not solely products of judicial ideology. The nature of the cases themselves – ranging from emergency docket rulings to high-profile constitutional challenges – influenced which interpretive modes became salient. The majority opinion in CASA, for example, drew out structural and historical reasoning, while avoiding moral or ethos-based appeals altogether.

This variability underscores the importance of measuring interpretive method not only as a window into judicial philosophy but also as a function of the cases the court chooses to hear. Across the term, these measurements allow scholars and others to observe interpretive alignment and divergence with new precision – making clear that in a polarized court, interpretive choices remain both deeply ideological and case-contingent.

A longer version of this post can be read at https://legalytics.substack.com/p/measuring-the-modes

Cases: Trump v. CASA, Inc.

Recommended Citation:

Adam Feldman,

The ways in which justices reach their decisions,

SCOTUSblog (Jul. 29, 2025, 12:15 PM),

https://www.scotusblog.com/2025/07/how-supreme-court-justices-reach-their-decisions/