ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Oct 9, 2024

at 5:16 pm

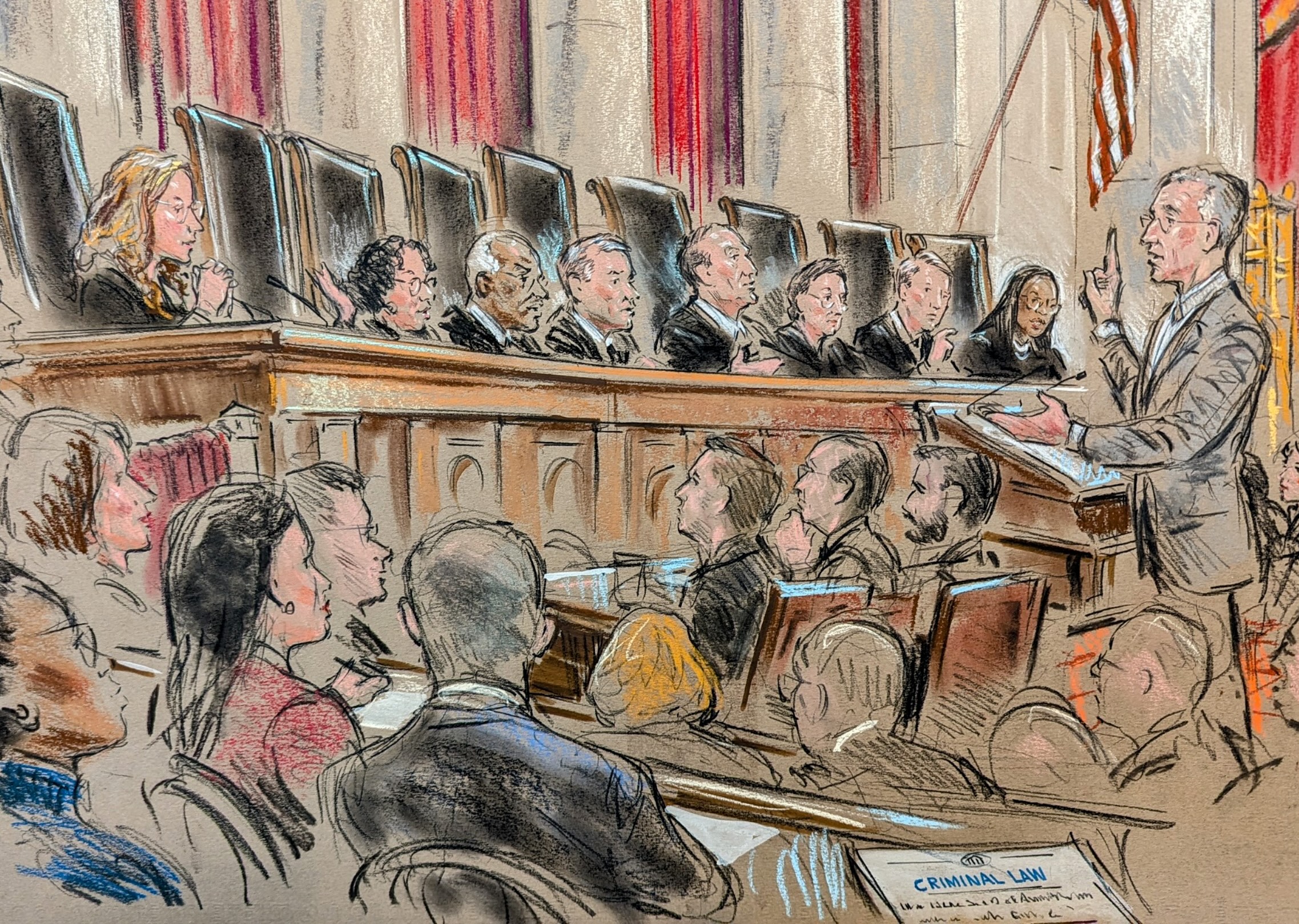

Seth Waxman argues for Richard Glossip. (William Hennessy)

Last year’s order putting Richard Glossip’s execution on hold to give the Supreme Court more time to consider his appeals would have required the votes of at least five justices, though which justices voted to take up the case was not made public. Glossip will need five votes again to prevail on his request to set aside his conviction and death sentence. That bid for a new trial is supported at the Supreme Court by Oklahoma’s Republican attorney general, Gentner Drummond. But after nearly two hours of oral arguments on Tuesday, it wasn’t clear where those five votes in favor of Glossip’s position might come from.

Richard Glossip was convicted and sentenced to death for his role in the 1997 murder of Barry Van Treese, who owned the Oklahoma City where he worked. Another man, occasional handyman at the motel Justin Sneed, confessed that he beat Barry Van Treese to death while on meth. Sneed testified that Glossip paid him to kill Van Treese. In exchange for his testimony, prosecutors promised Sneed that he himself would not face the death penalty.

Glossip has maintained his innocence for the nearly three decades he has been on Oklahoma’s death row. Last year he sought again to have his conviction and sentence set aside. He argued that in 2023, the state had for the first time given him files indicating that prosecutors knew, but failed to disclose to Glossip or his lawyers, that Sneed had been prescribed lithium for bipolar disorder after his arrest and had lied about it. Sneed had indicated that he had accidentally been prescribed the drug for a cold. Prosecutors also did not correct Sneed’s false testimony that he had never been treated by a psychiatrist.

Two different independent reports questioned the validity of Glossip’s conviction and death sentence. In June 2022, a 259-page report by a law firm hired by state legislators found “grave doubt as to the integrity of Glossip’s murder conviction and death sentence.†And after 600 hours of work Rex Duncan, a former district attorney and Republican legislator hired by Drummond, reported that he believed a new trial was necessary because Glossip had been deprived of a fair trial.

Duncan’s report prompted Drummond to join Glossip’s request for the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals, the state’s highest court for criminal cases, to set aside his conviction, as well as his plea for clemency from the state’s Pardon and Parole Board.

The court and the board both rejected Glossip’s requests for relief. But the Supreme Court agreed to put his execution on hold and, earlier this year, to take up his case.

The justices spent a significant amount of time on Wednesday grappling with a thorny but important procedural issue that they added to the case when they took up Glossip’s petition – whether they can review the state court’s decision at all, or instead are prohibited from doing so because that decision rests on an “adequate and independent state ground.†The Van Treese family, who support Glossip’s execution, have encouraged the justices to take the latter position and dismiss the appeal.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals held that Glossip’s claims were barred by a state law that prohibits courts in capital cases from reviewing issues that a prisoner could have raised earlier in the case.

But as far as Justice Sonia Sotomayor was concerned, this procedural bar was a non-issue (and the law could not serve as an adequate and independent state ground that would preclude the Supreme Court from weighing in) because the state had waived its right to rely on the law. (Under state law, the attorney general can give up its right to argue that the law on which the state court relied applies to ensure that justice is done.)

Representing Drummond, former U.S. solicitor general Paul Clement agreed. He pointed to a “hundred years of unbroken practice†of states waiving the right to rely on procedural bars that might otherwise prevent a case from going forward.

Christopher Michel, a former assistant to the U.S. solicitor general and a former law clerk to Chief Justice John Roberts, who was appointed by the court to defend the state court’s ruling after Oklahoma declined to do so, disputed whether the state had in fact waived its right to rely on the law. But Michel rejected any suggestion that Oklahoma courts have a longstanding practice of accepting waivers of procedural bars. Clement, he said, had offered only one case as an example of that practice, from 2005.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pushed back, asking Michel why he was looking only at cases involving “an attorney general who expressly waives a procedural bar.†Why not look more broadly, she queried, at what Oklahoma courts do whenever a party waives a procedural bar that is not jurisdictional – that is, does not concern the court’s authority to hear the case?

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, however, questioned that approach, countering that she was “wondering what the right sample size is.†Should the courts look at all waivers, she said, or just those involving the law at issue in this case?

Justice Elena Kagan appeared unconvinced that the state court’s decision rested on “independent†state grounds. She told Michel that the state court’s analysis of the underlying merits of Glossip’s claims were “intertwined†with its discussion of whether his claims should have been raised earlier and therefore were procedurally barred.

The state court’s opinion, Kagan observed, “starts with the substantive standard. Then it tells you that the State’s concession is wrong as a matter of law. Then, by the way, it tells you some stuff about the procedural bar standard. Then it goes back to the merits again.†And “it’s a high bar,†she emphasized, “to say that something is independent.†“We do not give that benefit of the doubt to the state,†she concluded.

But Justice Samuel Alito was more sympathetic to Michel’s argument. He noted that the state court had indicated that even if Glossip’s claim “overcomes the procedural bar, then†he still loses. Why, Alito asked, wouldn’t that be a clear statement that the state court’s ruling rested on adequate and independent state grounds?

Glossip’s lawyer, former U.S. solicitor general Seth Waxman, responded that the same decision then discussed the merits of Glossip’s claim that prosecutors had violated the Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in Brady v. Maryland, which requires them to turn over any evidence that is favorable to the defendant and could affect the decision about guilt or punishment. Alito appeared unmoved.

Glossip contends that prosecutors violated not only Brady but also the court’s 1959 decision in Napue v. Illinois, holding that if prosecutors obtain a conviction using what they know is false testimony, the conviction must be set aside if there is “any reasonable likelihood†that the false testimony could have affected the jury’s decision.

Chief Justice John Roberts, however, appeared skeptical. He asked Waxman whether it would have actually made a difference if the jury had known that Sneed had received lithium from a psychiatrist, rather than from some other physician.

Waxman stressed that there were other problems as well, including that Sneed “lied and was allowed to lie when he said that he never saw a psychiatrist,†that “very well could have made a significant difference in the outcome of the case.†Sotomayor cut him off, directing him to his side’s own point – that what mattered was not the drug but the bipolar diagnosis that the jury didn’t know about, which the drug was meant to treat. The bipolar disorder and the possibility of related violent behavior, Sotomayor emphasized, was evidence that “would have explained the murder.â€

Justice Brett Kavanaugh appeared somewhat open to Glossip’s argument, telling Michel that he was “having some trouble†with Michel’s argument that it wouldn’t have mattered to the jury if it had known that Sneed was bipolar and had testified falsely, “when the whole case depended†on Sneed’s credibility. Would it make a conviction more likely, Kavanaugh asked, if the jury knew that Sneed lied on the stand and suffered from bipolar disorder, “creating all sorts of avenues for questioning his credibility�

Michel answered that Glossip had made a strategic decision not to raise arguments about Sneed’s mental health. And in any event, with “lots of other evidence†implicating Glossip that did not involve Sneed, Michel said, “it’s difficult to say the jury would have rejected†Glossip’s “central defense†that he was not involved in the murder itself “and yet turned around and accepted it if only it knew that Justin Sneed allegedly saw a psychiatrist.â€

Clement countered that if a key witness lies on the stand, there is a “reasonable probability†of a different result, including because it undermines that witness’s credibility. Psychiatric experts could have testified about Sneed’s propensity to act violently and impulsively, Clement suggested.

Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas both questioned whether Glossip and the state were reading too much into the prosecutors’ notes that, they say, supports their allegations that prosecutors knew but failed to disclose that Sneed had been prescribed lithium by a psychiatrist for bipolar disorder after his arrest.

Both justices characterized the notes – which contain the phrase “on Lithium?†and a reference to a “Dr. Trumpet†(when the psychiatrist’s name was Dr. Trompka) – as “cryptic.†Alito told Waxman that a “friend of the court†brief filed by Van Treese’s family provides a “pretty compelling†counternarrative to explain the notes, while Thomas told Clement that he “couldn’t make heads or tails†of the handwritten notes.

And Thomas expressed broader concerns that the prosecutors originally involved in Glossip’s case believe that they have been “frozen out†of the process, without being provided an “opportunity to give detailed accounts of what those notes meant and what they did during the trial.†“It seems,†he added, “as though their reputations are being impugned.â€

Clement pointed to the two independent investigations, conducted by Duncan and the law firm Reed Smith. However, noting the “pretty significant factual questions†remaining in the dispute, Jackson wondered aloud whether an evidentiary hearing might be an appropriate next step in the case – to determine, for example, what prosecutors knew and what their notes meant.

All three lawyers appearing before the court on Wednesday told the justices that such a hearing was not necessary. But with Justice Neil Gorsuch recused from the case, it might give the eight-member court a way to avoid deadlocking. A 4-4 decision from the Supreme Court would leave the state court’s ruling against Glossip in place.

This article was originally published at Howe on the Court.