SYMPOSIUM

on Feb 4, 2022

at 3:31 pm

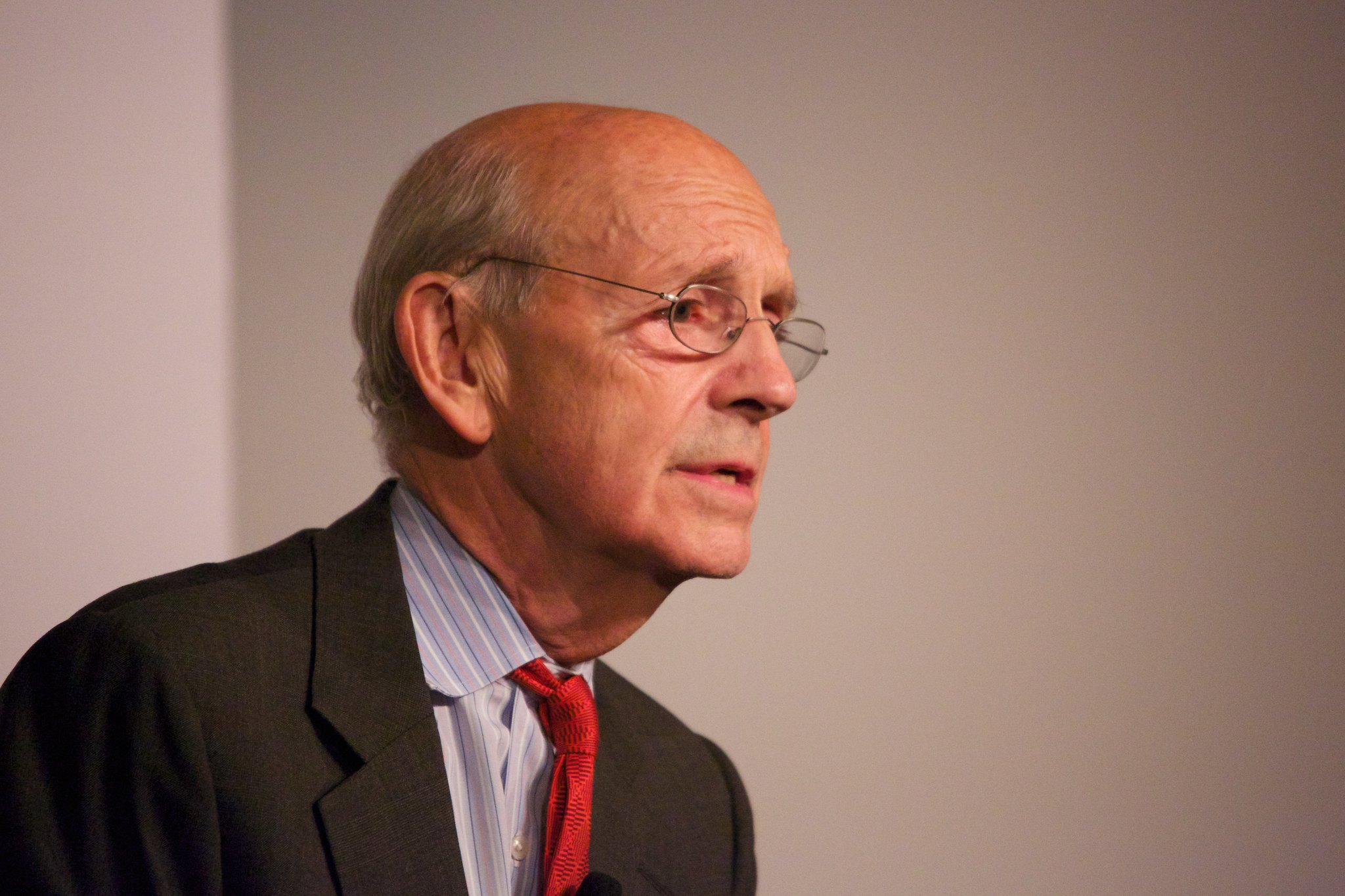

Justice Stephen Breyer delivers a lecture on the rule of law in Washington, D.C. in 2013 at an event sponsored by the Salzburg Global Seminar. (Salzburg Global Seminar via Flickr)

This article is part of a symposium on the jurisprudence of Justice Stephen Breyer.

Brent Newton is a visiting professor of law at Penn State-Dickinson School of Law. He previously taught seminars on Breyer’s jurisprudence at American University Washington College of Law.

Two spectrums exist among Supreme Court justices, particularly those who have served since the New Deal ushered in the modern America. One is the well-known liberal-conservative ideological continuum. Among modern justices, Clarence Thomas exemplifies the conservative pole, while Thurgood Marshall exemplified the liberal pole. A different, less-discussed spectrum is the idealogue-pragmatist continuum. Thomas and Marshall both have occupied the ideological end of this measure. At the opposite end of the second spectrum have been pragmatic justices such as Sandra Day O’Connor and Lewis Powell.Idealogues have sought to reshape the court’s jurisprudence in their own ideological vision, whether liberal or conservative, often at the expense of stare decisis and typically voiced most vigorously in dissenting opinions. Think of Marshall and William Brennan in death-penalty cases. Conversely, pragmatists, who necessarily are ideological moderates, have striven for small steps in the court’s jurisprudential evolution and often have been the swing votes – most visibly as the authors of pivotal concurring-in-judgment opinions. These pragmatists consider the real-world consequences of the court’s decisions and value stare decisis and narrow rulings. Think of O’Connor or Anthony Kennedy in abortion-rights cases.

Ideologically, Stephen Breyer generally has been a moderate-liberal – although more accurately characterized as a moderate when viewed in the context of all justices since the 1930s. On the second spectrum, he is more of a pragmatist than an idealogue.

An ideological moderate

Empirical political scientists use an ideological ranking of justices called the Martin-Quinn score. A positive score reflects a conservative ideology, while a negative score reflects a liberal ideology. The scale is based on justices’ votes in a wide variety of types of cases. Although an imperfect ideological measure, because it simply considers positive or negative voting patterns (e.g., votes for or against criminal defendants in criminal procedure cases) and fails to account for the often nuanced reasons behind the votes, the scale tends to be generally accurate. For instance, Thomas’ score for his time on the court generally has been above 3.0, while Marshall’s scores generally fell below -3.0.

The graphic below demonstrates the MC scores for all justices since 1935. It was prepared by Randy Schutt using the Martin-Quinn dataset.

Click to enlarge.

Although Breyer’s score (ranging between 0.0 and -2.0 over his 25-year tenure) indicates a moderate-liberal ideology today, it actually is more moderate when considered in the broader context of all justices since 1935. For instance, MQ scores for William Douglas fell to -8.0 at the end of his tenure, and Marshall fell below -4.0. Scores for Thomas and William Rehnquist both were at or above 4.0 for numerous terms. Breyer sometimes has voted in a manner that has disappointed liberals. For instance, as I have written elsewhere, his votes in Fourth Amendment cases have been closer to Antonin Scalia’s than to those of liberal justices. And although Breyer’s score has gotten somewhat more liberal, his changing score may reflect that the court itself has grown more conservative during his tenure, including in its selection of the types of cases to hear.

The pragmatist

Breyer’s pragmatic record as a justice can be understood by examining the variety of legal jobs he had before becoming a justice, which honed his pragmatic view. After clerking for Arthur Goldberg, Breyer worked in the Justice Department – in the antitrust division and on the Watergate task force. After that, he became a full-time academic. Although he was a tenured Harvard law professor, his area of expertise was administrative law, one of the more pragmatic fields. He also was a faculty member at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, which removed him from the ivory tower and focused him on real-world issues.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Breyer served in key policy-making roles in the federal government before becoming a justice. While on leave from Harvard, he served as a senior legal adviser in the Senate. He played a key role in creating legislation that deregulated the airlines. And, while serving on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, he played a highly influential role in creating the Federal Sentencing Guidelines as an original member of the U.S. Sentencing Commission. Those experiences taught Breyer both how to compromise and to rely on data rather than ideology. His work on Capitol Hill taught him about the political realities of legislation and made him more willing to look at the history and purpose of legislation rather than solely at its plain language.

Breyer believes that courts should consider a wide variety of sources of information in reaching decisions – well beyond the traditional judicial tools such as precedent and statutory interpretation canons. He advocates that, in appropriate cases, judges should be informed by both the hard and soft sciences, such as economics, in reaching decisions. He also has been concerned with the real-world consequences of judicial decisions and the “administrability” of judicially created rules. Finally, reflecting his broader worldview, Breyer does not believe that the United States has a monopoly on judicial wisdom.

Even in death-penalty cases, in which Breyer superficially resembles Marshall and Brennan by coming close to calling for the outright abolition of capital punishment as systemically unconstitutional, his reasons are less ideological and more pragmatic. Chief among his reasons are the systemic delays in carrying out executions – which, as he wrote in a 2020 dissent, undermine the purposes of capital punishment.

In sum, decades from now, I believe that Breyer will be best known for having been a moderate pragmatist, a justice not driven primarily by ideology but more by well-informed pragmatism.