ARGUMENT ANALYSIS

on Dec 9, 2021

at 7:34 pm

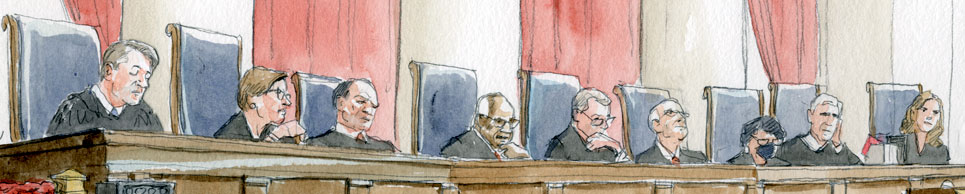

On Wednesday, the court heard oral argument in Shinn v. Ramirez and Jones, two death penalty cases that will determine whether prisoners may develop new evidence to support claims that their lawyers were constitutionally ineffective at trial. The argument was notable because a surprising group of justices appeared genuinely to struggle with the legal issue at the heart of the case – repeatedly calling it “rather odd,†“very odd,†“close,†and “really a tough case.†In particular, a trio of conservatives – Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh – seemed sympathetic to both sides and at times wondered aloud how they should even approach deciding the issue. As Roberts put it, what should the court do in a situation where “the plain language†of a statute “seems to require one result,†while “the plainly logical meaning of a subsequent precedent†seems to require the opposite?

To recap the issue in the two cases: A 1996 statute, the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, bars federal courts from holding evidentiary hearings in habeas corpus cases if a prisoner “has failed to develop the factual basis of a claim in State court [post-conviction] proceedings.†But a 2012 Supreme Court decision, Martinez v. Ryan, held that a prisoner could raise new claims of ineffective assistance of trial counsel if her lawyer in those state court post-conviction proceedings was himself ineffective. The question raised in Shinn v. Ramirez and Jones is: If Martinez allows the prisoner to raise the claim, does AEDPA nevertheless prohibit her from developing evidence to support it?

Arizona Solicitor General Brunn Roysden III started out, predictably, by emphasizing AEDPA’s text, arguing that the issue before the court is “fundamentally a question of statutory interpretation.†He acknowledged early on that the statute’s strict terms could lead to unjust results, stating “that no fact-finder could have found the prisoner guilty is not enough†to overcome AEDPA’s hurdles. In other words, it does not matter if the prisoner is actually innocent, as the lower courts found in the case of Barry Lee Jones. If Jones “failed to develop†the evidence of his trial lawyer’s ineffectiveness in state court, the federal courts are powerless to alter his conviction and death sentence.

Thomas began the questioning by calling it “rather odd†that courts could allow a prisoner to raise a claim but not allow him to develop the evidence for the claim. He stated that Arizona’s position would render Martinez “pretty worthless.†Notably, Thomas was one of two dissenters in Martinez and has been unperturbed by rendering decisions he disagrees with “pretty worthless†in other contexts. Nevertheless, he appeared uncomfortable with Arizona’s contention that the court should simply disregard its precedent in this case – or, at least, his questions were designed to address (and perhaps assuage) any such discomfort.

Roberts noted that it’s a “basic syllogism†that “if you do get the right to raise the claim for the first time, because your counsel was incompetent before, surely you have the right to get the evidence that’s necessary to support your claim.†He seemed firmly unpersuaded of the state’s position, even if it had grounding in the statute’s text.

Kavanaugh’s questions suggested he was genuinely wrestling with how to decide the issue. He repeatedly expressed uncertainty about both sides’ positions, calling the case a “close†one, and making each side’s argument against the other. Following Roberts and Thomas, he asked Roysden about his position, “Doesn’t it really gut Martinez in a huge number of cases? And then what’s the point of Martinez?†Roysden responded that to the extent Martinez cannot be reconciled with AEDPA, it should be overruled. Kavanaugh shot back, “Assuming we don’t do that, what’s your next answer?â€

But this unexpected trio of justices similarly struggled with Ramirez and Jones’ position that AEDPA’s “failed to develop†language does not present a barrier to the court ruling in their favor. Appearing for the two prisoners, Robert Loeb argued that the statutory language should be interpreted through the lens of the court’s precedents, including Martinez, to require a finding of fault by the prisoner, and that where the prisoner’s lawyer had been constitutionally ineffective, the lawyer could not be treated as an agent of the prisoner. Just as he had called Arizona’s position “rather odd,†Thomas noted that this position, too, was “a bit odd†in that it would appear to “eviscerate the restrictions of AEDPA.â€

Roberts asked if any precedent could guide the court in deciding how to reconcile the “plain language of the statute†with the “plainly logical meaning†of Martinez. Loeb responded, “I don’t have a case that’s going to satisfy you on that,†but argued that “Congress would have anticipated that if you weren’t going to be held at fault for failing to bring the claim, you weren’t going to be held at fault for failing to develop the claim.†Roberts replied, “That’s a lot of prescience to ascribe to Congress.â€

Loeb ultimately argued that the fault really lay with Arizona, since it required defendants to wait until the post-conviction stage – when they have no right to counsel – to argue that trial counsel was ineffective. The state, he said, could not deprive prisoners of one fair and full opportunity to litigate that constitutional claim simply by slapping the label “post-conviction†on the stage of the litigation in which that claim could be raised. That particular feature of Arizona’s criminal procedure was part of what prompted the court to create the Martinez exception to the procedural default rule in the first place.

Kavanaugh asked Loeb whether the fact that Arizona has a separate procedural mechanism for raising an actual innocence claim resolves that problem with its state court procedure. Loeb responded, “Whether you are innocent or guilty, you have a right to a fair hearing.†He then put it in terms that seemed specifically geared toward Kavanaugh, who coaches his daughters’ basketball team and has shown himself fond of basketball metaphors on the bench, stating: “It’s like them saying if you’re coaching a basketball game and one team gets five players and one team gets one player, and we’re going to play the game, but at the end of the game we’re going to give [the team with one player] a shot from half court, and that’s going to make the game fair. That doesn’t make the game fair, Your Honor.â€

The three other justices who asked questions during the argument made their views clear, and their positions were unsurprising. Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan indicated agreement with Ramirez and Jones’ position that the statute must be read in conjunction with the court’s precedents. As Sotomayor put it, “The statute doesn’t define what ‘at fault’ means … So, by definition, what constitutes fault is defined by us, correct?†Justice Samuel Alito at first appeared to channel the concerns of his ambivalent conservative colleagues, saying “this is really a tough case†because adopting Arizona’s position “would drastically reduce what a lot of the lower courts have thought Martinez means.†But this really tough case proved no match for Alito, who in the next breath stated, “The fact remains that we have to follow the federal habeas statute. We have to follow AEDPA.†Notably, Alito joined the majority in Martinez but showed no interest in extending it to assist the prisoners here.

Justices Stephen Breyer, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett asked no questions during the argument. It’s a safe prediction that Breyer and Gorsuch will split their votes between the prisoners and the state, respectively, so the case will likely come down to two of the three justices who were on the fence.