CASE PREVIEW

on Apr 15, 2022

at 3:11 pm

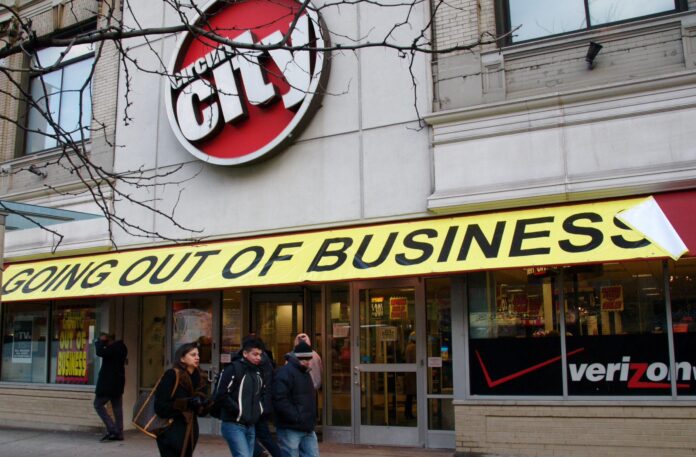

Circuit City Stores paid over half a million dollars more in bankruptcy fees than it would have by filing in a different district. (Ed Yourdon via Wikimedia Commons)

Monday’s argument in Siegel v. Fitzgerald brings the justices a fun little dispute: whether Congress violated the Constitution’s bankruptcy clause – which authorizes “uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States – when it created two separate systems for administering business bankruptcy cases, with markedly lower fees in Alabama and North Carolina than in the remainder of the nation.

The summary should make the average reader wonder how such a bizarre system could arise, but it is just a typical narrative of the gross dysfunction that plagues bankruptcy legislation. We can start with the adoption of the Bankruptcy Code in 1978, which included a pilot program for United States trustees, who would perform administrative tasks in bankruptcy cases formerly performed by bankruptcy judges. Those trustees would work in an Executive Office for United States Trustees, a component of the Department of Justice. When the program succeeded, it was made permanent and extended nationwide. Well, not quite. A small group of bankruptcy judges in six of the 90-odd judicial districts nationwide, backed by their senators (in Alabama and North Carolina) managed to have their districts excluded from the U.S. Trustee Program. Judicially appointed bankruptcy administrators perform the administrative work of trustees in those six districts.

Congress has funded the U.S. Trustee Program with user fees paid by the companies that file for bankruptcy. As it commonly does, Congress has required that the program be self-funding, so the fees rise as the costs of the program rise. The bankruptcy administrator program, by contrast, is not separately funded, but does charge fees set by the Judicial Conference (the administrative component of the federal judicial system).

The case arises out of a provision in the Bankruptcy Judgeship Act of 2017, which responded to a shortfall in funding for the U.S. Trustee Program by requiring a five-year increase in the fees businesses pay. The increase was steep for large businesses, as it increased the maximum fee from $30,000 to $250,000. Because the Judicial Conference did not promptly raise its fees to the same level, debtors in U.S. trustee districts paid higher fees than debtors that filed in administrator districts, a total of about $100 million before the disparity was rectified. The case before the court involves a representative large debtor – Circuit City Stores – that paid about $600,000 more in fees than it would have paid if it had filed in an administrator district.

With little Supreme Court precedent – Congress hasn’t made a practice of writing different bankruptcy laws for different parts of the country – it is not entirely clear what to expect on this one. The arguments, though, are easy to understand. Alfred Siegel (trustee for the Circuit City estate) presents a simple textual argument. First, the statute setting different fees for trustee districts and administrator districts is a “La[w] on the subject of Bankruptciesâ€; it is the law that sets the fees that companies pay when they file seeking bankruptcy relief. Second, it was not “uniform … throughout the United States,†because debtors that filed during 2018 paid millions of dollars more if they didn’t file in Alabama or North Carolina than they would have paid if they had filed in those states.

The government (defending Congress’ handiwork) offers several justifications for the arrangement. First, it argues that legislation about “administrative aspects†is not the kind of “Law†that needs to be uniform because it is not a law on the “subject of Bankruptcies.†The government emphasizes early practice permitting bankruptcy judges to set fees on a district-by-district basis, which led to variations in fees in the early 19th century, and contends that a requirement of uniformity that goes to the level of fees would be heedlessly impractical. The government justifies the U.S. Trustee Program under congressional power “[t]o constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court,†reasoning that a statute designed to enhance the efficiency of the bankruptcy courts falls well within that power.

The government also argues, strangely, that the program is constitutional because Congress did not pass a law that obligated anybody to charge different fees. At all times the Judicial Conference could have charged the same fees as Congress mandated for the U.S. Trustee program, so Congress can’t be blamed for lack of uniformity when it adopted the challenged statute. That argument, to my mind, is a bit difficult to follow, because the government cannot deny in fact that the fee schedule Circuit City faced in 2018 was higher than the fee schedule in the administration districts, that Circuit City in fact would have paid lower fees had it filed in one of those districts, and that the reason for the difference is that Congress wrote a mandatory high-fee statute for trustee districts and a discretionary-fee statute for administration districts.

As I mentioned above, there is not a lot of directly relevant precedent, so it is a little difficult to be sure how the justices will react. In an earlier era, you would have expected the justices to bend over backward to defer to Congress before invalidating a federal statute as unconstitutional, but I would not expect that to be an important reaction at Monday’s argument. The real question will be how many of them prefer to take the simple textual path that Siegel offers. I should be able to write more about that in just a few days.